OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) are a modern goal-setting and execution framework designed to turn strategy into measurable outcomes—and this guide covers the full arc of What are OKRs, from the History of OKRs (Andy Grove at Intel to John Doerr and Google) to a clear Definition of OKRs, the core Benefits of Using OKRs, and practical OKR Examples you can model immediately. You’ll also learn the real distinction in OKR vs KPI, plus how OKRs compare in a wider management landscape—OKR vs KPI vs MBO vs Balanced Scorecard: A Broader Comparison—so you can choose (and combine) the right system for monitoring performance, driving change, and aligning teams around what matters most.

The History of OKRs: From Intel to Google to Global Adoption

The inventor: Andy Grove at Intel (1970s)

The story of OKRs begins with Andy Grove, co-founder and CEO of Intel, who developed the framework in the 1970s. Grove recognised that existing goal-setting methods — particularly Peter Drucker’s MBO (Management by Objectives) system — were too rigid, too annual, and too top-down to keep pace with Intel’s fast-moving semiconductor business. He needed a system that combined ambitious goal-setting with measurable outcomes and frequent recalibration.

Grove’s innovation was structural: pair a qualitative, inspiring Objective with a small set of quantitative Key Results, review progress frequently, and make everything transparent across the organisation. He originally called this system “iMBOs” (Intel Management by Objectives) before the terminology evolved into what we now know as OKRs.

One of the earliest high-stakes demonstrations of OKRs at Intel was Operation Crush in 1980 — Intel’s strategic campaign to reclaim the microprocessor market from Motorola. Using OKRs, Grove aligned engineering, sales, marketing, and manufacturing teams around a single objective with clear, measurable key results. The campaign succeeded and is widely credited with establishing Intel’s market dominance — and with proving OKRs as a framework that could coordinate complex, cross-functional execution at speed.

The evangelist: John Doerr brings OKRs to Google (1999)

John Doerr, a venture capitalist at Kleiner Perkins, learned OKRs directly from Andy Grove while working at Intel in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Doerr became an early investor in Google in 1999 and introduced OKRs to Larry Page and Sergey Brin when the company had fewer than 40 employees. The framework gave Google a disciplined mechanism for setting ambitious goals, maintaining strategic focus, and scaling rapidly without losing alignment.

Google’s adoption of OKRs became one of the most influential case studies in modern management. The company used OKRs to coordinate the development of products like Gmail, Chrome, and Android — each requiring cross-functional collaboration at massive scale. Doerr later documented Google’s OKR journey and his broader philosophy in his 2017 bestseller Measure What Matters, which introduced the framework to a global mainstream audience and popularised the concept of OKR superpowers (the FACTS framework: Focus, Alignment, Commitment, Tracking, and Stretching).

The global expansion: Beyond Silicon Valley (2010s–present)

Google’s visible success sparked a wave of adoption — first among Silicon Valley technology companies like LinkedIn, Twitter, Spotify, and Uber, and then across industries worldwide. By the mid-2010s, OKRs had moved well beyond tech:

- Enterprise and manufacturing: Companies like Samsung, BMW, and Deloitte adopted OKRs to drive innovation alongside operational excellence.

- Non-profits and government: The Gates Foundation famously uses OKRs to track progress on global health and education initiatives. Government agencies in several countries have adopted the framework for public service delivery goals.

- Startups and scale-ups: For resource-constrained organisations, OKRs provide the focus and alignment discipline that prevents the “doing everything, achieving nothing” trap that kills early-stage companies.

Google’s adoption of OKRs became one of the most influential case studies in modern management. The company used OKRs to coordinate the development of products like Gmail, Chrome, and Android — each requiring cross-functional collaboration at massive scale. Doerr later documented Google’s OKR journey and his broader philosophy in his 2017 bestseller Measure What Matters, which introduced the framework to a global mainstream audience and popularised the concept of OKR superpowers (the FACTS framework: Focus, Alignment, Commitment, Tracking, and Stretching).

The evolution continues: OKRs in 2025 and beyond

Today, OKRs are no longer just a Silicon Valley export — they are a globally recognised management operating system used by organisations of every size and sector. The framework itself has continued to evolve:

- CFRs (Conversations, Feedback, Recognition) have emerged as the essential companion to OKRs, forming what Doerr calls Continuous Performance Management — replacing static annual reviews with an ongoing rhythm of coaching and dialogue.

- AI-powered OKR tools now assist with goal drafting, progress prediction, alignment mapping, and initiative recommendation — making the framework more accessible and data-driven than ever.

- Remote and hybrid work has amplified the need for outcome-based goal frameworks. When you can’t measure presence, you must measure results. OKRs are perfectly designed for this shift.

The core principles Andy Grove established in the 1970s remain remarkably intact: set a small number of ambitious goals, measure them with quantifiable results, review progress frequently, and make everything transparent. What has changed is the scale of adoption, the sophistication of supporting tools, and the depth of practice knowledge accumulated across thousands of implementations worldwide.

Definition & DNA of OKRs

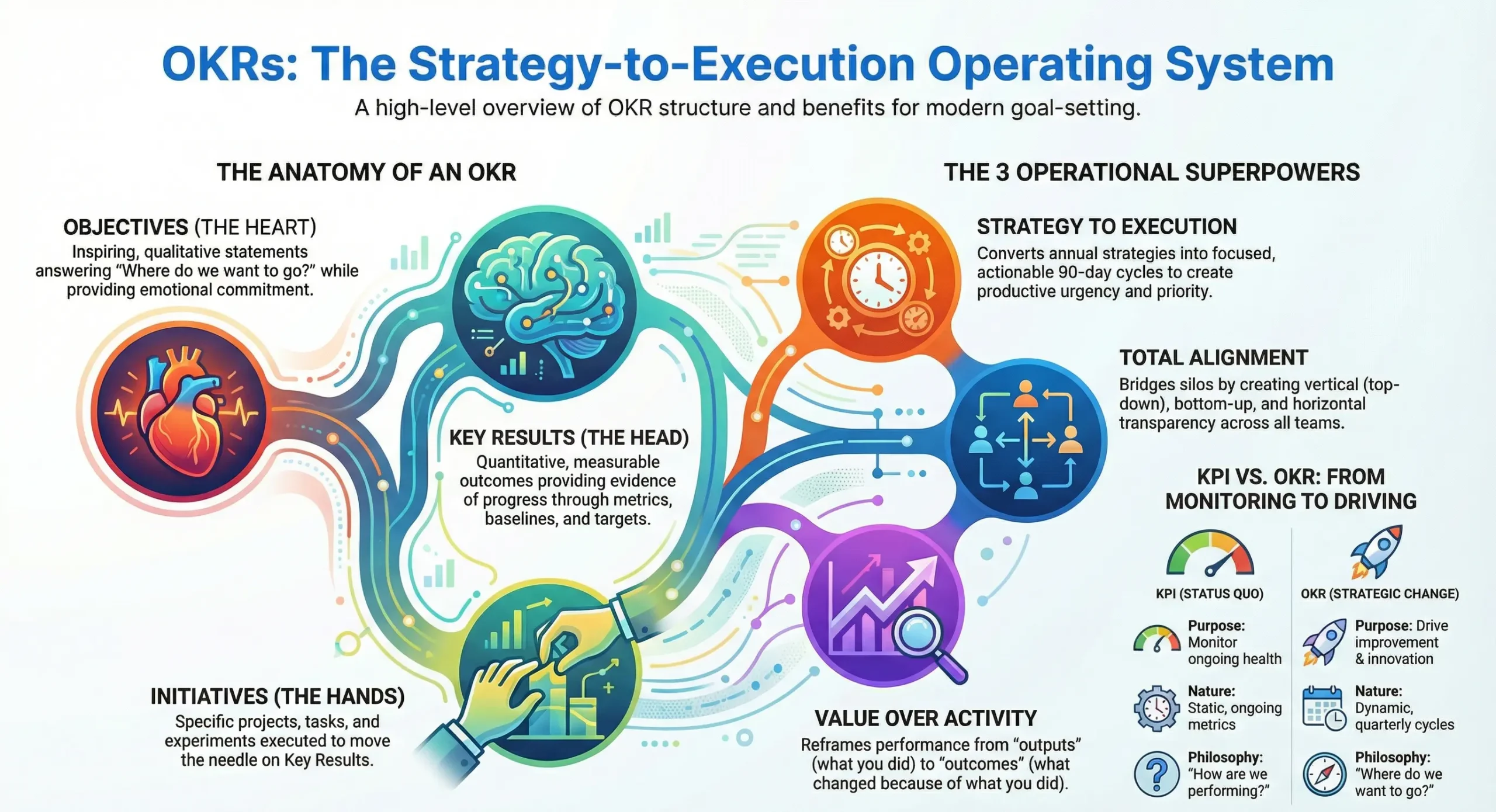

The OKR Definition

OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) are a goal management and execution framework in which teams or individuals set no more than 3 to 5 Objectives for a given cycle, with no more than 3 to 5 measurable Key Results per Objective, supported by Initiatives that drive execution. — Nikhil Maini, CEO – OKR International

Or, as John Doerr’s classic formula puts it: “I will [OBJECTIVE] as measured by [KEY RESULTS].”

The framework is deceptively simple. An OKR has three interdependent components — Objectives, Key Results, and Initiatives — each serving a distinct function. At OKR International, we describe these three components as the DNA of every OKR, using a body metaphor that has helped thousands of practitioners internalise the framework:

- Objectives are the Heart — they provide direction and inspiration

- Key Results are the Head — they provide measurement and evidence of progress

- Initiatives are the Hands — they get the actual work done

All three components work in tandem. Remove any one of them and the OKR breaks down: an Objective without Key Results is a wish; Key Results without an Objective are disconnected metrics; and Key Results without Initiatives are hopes with no plan of action. Let’s examine each in depth.

Objectives: The Heart of Your OKRs

An Objective answers the most fundamental strategic question: “Where do we want to go?”

Objectives are qualitative, directional statements that define what you want to achieve. When well-crafted, they are ambitious enough to stretch the team, clear enough to be understood by anyone in the organisation, and inspiring enough to create emotional commitment. This is why we call them the heart of OKRs — they bring purpose and emotionality to what could otherwise be a dry planning exercise.

Characteristics of a well-written Objective:

- Qualitative, not quantitative. An Objective describes a desired future state in words, not numbers. The numbers belong in the Key Results. “Become the most customer-centric company in our sector” is an Objective. “Achieve 90% customer satisfaction” is a Key Result.

- Ambitious yet achievable. Objectives should push the team beyond business-as-usual without being delusional. The best Objectives sit in the zone between “this will be hard” and “this is impossible.” Google distinguishes between two types: committed Objectives (roofshot OKRs — expected to be fully achieved at 100%) and aspirational Objectives (moonshot OKRs — where achieving 60–70% is considered a strong result). A healthy OKR set typically includes a mix of both.

- Action-oriented. Objectives should start with strong action verbs — build, launch, transform, establish, dominate, create, accelerate, deliver. Passive language produces passive execution.

- Time-bound. Objectives are set for a defined cycle — typically a quarter for tactical OKRs and a year for strategic OKRs. This time constraint creates productive urgency. Annual Objectives are then broken into quarterly ones, creating a natural rhythm of planning and execution.

- Derived from strategy, not created from thin air. Every Objective must trace its lineage back to the organisation’s vision, mission, values, and strategy. An Objective that cannot be connected to a strategic priority is, by definition, not a priority.

Objective categories. While Objectives can address virtually any strategic area, they typically revolve around core themes such as customer experience, revenue growth, operational performance, employee engagement, product innovation, or market expansion. At the company level, 3–5 Objectives per year or quarter set the strategic direction. At the team level, Objectives should clearly contribute to one or more company-level Objectives.

A common mistake: Writing Objectives that are actually tasks or projects. “Implement a new CRM system” is a project (and belongs in Initiatives). “Transform our customer relationship management into a competitive advantage” is an Objective. The test is simple: does this statement inspire a team to figure out how to achieve it, or does it merely describe what to do? If the latter, it’s not an Objective.

Key Results: The Head of Your OKRs

If Objectives answer “Where do we want to go?”, Key Results answer the equally critical question: “How will we know we’re getting there?”

Key Results are quantitative, measurable outcomes that, when achieved, directly advance the Objective. They are the evidence of progress — the head of your OKR — bringing rigour and accountability to what would otherwise be an inspirational but unmeasurable aspiration.

Characteristics of well-written Key Results:

- Measurable and verifiable. There must be no grey area. At the end of the cycle, you can look at each Key Result and clearly determine: did we achieve this or not? As Andy Grove said: “Yes? No? Simple. No judgments in it.”

- Every Key Result has a metric, a baseline, and a target. “Improve customer satisfaction” is not a Key Result — it has no metric, no starting point, and no target. “Increase NPS from 32 to 55” is a proper Key Result — you know exactly what you’re measuring (NPS), where you’re starting (32), and where you need to be (55).

- Outcome-based, not activity-based. This is the single most important principle and the most frequently violated. “Conduct 20 customer interviews” is an activity — it belongs in Initiatives. “Reduce customer churn from 8% to 3%” is an outcome — it belongs in Key Results. The test: does this measure what changed, or what we did? Activities are inputs. Outcomes are impacts.

- Challenging but not delusional. Key Result targets should stretch the team. For aspirational (moonshot) OKRs, achieving 60–70% of the target is considered a good outcome. For committed (roofshot) OKRs, 100% achievement is expected. If you’re consistently hitting 100% on all Key Results, your targets aren’t ambitious enough.

- Limited to 3–5 per Objective. This constraint forces prioritisation. If you have 8 Key Results under a single Objective, you haven’t been rigorous enough about identifying what truly matters.

The interactivity principle

This is a concept that most OKR guides overlook and it’s critical. When you write 3–5 Key Results under an Objective, those Key Results are not independent checkboxes — they are interdependent and mutually reinforcing. Their cumulative, combined effect is what achieves the Objective. Think of them as a system, not a list.

For example, under the Objective “Deliver an onboarding experience users love”:

- KR1: Increase Day-7 activation rate from 28% to 55%

- KR2: Reduce onboarding drop-off from 42% to 12%

- KR3: Achieve onboarding satisfaction score of 4.6/5

You can’t sustainably raise activation (KR1) without reducing drop-off (KR2), and both ultimately drive satisfaction (KR3). These Key Results interact as a system. Achieving any one in isolation, while the others stagnate, is unlikely to realise the Objective.

The three patterns of Key Results

Most Key Results fall into one of three patterns:

- Increase something: Grow revenue, raise NPS, improve activation rate

- Decrease something: Reduce churn, shorten cycle time, lower defect rate

- Guardrail (maintain) something: Sustain quality while scaling, keep employee satisfaction above a threshold while implementing change

The guardrail pattern is often overlooked but essential. It prevents teams from optimising one metric at the expense of another — for example, reducing time-to-hire without accidentally lowering candidate quality.

Scoring Key Results.

At the end of each OKR cycle, Key Results are scored to evaluate progress. The most common approaches are:

- 0.0 to 1.0 scale (Google’s method): 0.7 is the target for aspirational Key Results; 1.0 is expected for committed ones

- Percentage completion: 0–100% progress tracking

- Traffic light system: Red (failed to make meaningful progress), Yellow (made progress but fell short), Green (achieved or exceeded)

The scoring is not about judgement — it’s about learning. A score of 0.6 on an aspirational OKR isn’t failure; it’s data that informs the next quarter’s planning.

Initiatives: The Hands of Your OKRs

With an Objective set and Key Results defined, the final question is: “What do we need to do to move the needle on these Key Results?”

Initiatives are the projects, tasks, experiments, and activities that drive execution. They are the hands of your OKR — they get things done. Without Initiatives, an OKR is a measurement system with no engine. Without Key Results, Initiatives are activities with no compass.

Characteristics of well-designed Initiatives:

- Directly connected to a Key Result. Every Initiative must have a clear hypothesis: “We believe doing X will move Key Result Y.” If you cannot articulate this connection, the Initiative doesn’t belong in this OKR.

- At least one Initiative per Key Result. In practice, you’ll often have multiple Initiatives per Key Result, especially at the start of a quarter when you’re testing several approaches simultaneously.

- Within your circle of influence. Initiatives must be things your team can actually execute. If an Initiative depends entirely on another team’s action and you have no ability to influence it, it’s not a viable Initiative for your OKR — it’s a dependency that needs to be addressed through cross-functional alignment.

- Can be Boolean or metric-driven. Some Initiatives are binary: “Launch the redesigned onboarding flow — Yes/No.” Others are metric-driven: “Publish 12 pillar articles this quarter.” Both are valid.

The most important principle about Initiatives: treat them as hypotheses, not commitments.

This is where OKRs fundamentally diverge from traditional project management. When you set Initiatives at the start of a quarter, you are essentially placing bets — hypothesising that these specific actions will move the Key Results. Some bets will pay off. Others won’t. The discipline is in detecting which ones aren’t working and recalibrating quickly.

At OKR International, we teach the add-modify-delete approach for Initiative management:

- Add an Initiative that’s been missing — perhaps a new approach you hadn’t considered

- Modify an existing Initiative that’s partially working but needs adjustment

- Delete an Initiative that’s proven to be a dead-end — don’t keep investing in something that isn’t yielding results simply because you committed to it at the start of the quarter

The more frequently you review your Initiatives — ideally in weekly or biweekly check-ins — the more opportunities you have for course correction. This review cadence is the engine room of OKR execution and is the primary reason why most traditional goals (and New Year’s resolutions) go unachieved: they are set and forgotten, with no mechanism for ongoing adaptation.

The stability spectrum

There’s an important hierarchy of stability across the three OKR components:

- Objectives should be the most stable — they rarely change within a quarter unless there’s a fundamental strategic shift

- Key Results are moderately stable — the metrics shouldn’t change, though targets may occasionally be recalibrated mid-quarter if circumstances shift dramatically

- Initiatives are the most dynamic — they should be reviewed and adjusted frequently based on what’s working and what isn’t

Or, as we summarise it for our coaching clients: “Be passionate about your Objectives. Be dispassionate about your Initiatives.”

How Objectives, Key Results, and Initiatives Work as a System

To see the full DNA in action, here’s a complete OKR with all three components:

Objective

Build the healthiest, most engaged workforce in our industry.

Key Results:

- KR1: Increase employee engagement score from 62 to 82

- KR2: Reduce voluntary attrition from 22% to 10%

- KR3: Achieve 90% participation rate in professional development programmes (currently 35%)

Initiatives for KR1 (Engagement):

- Launch monthly town halls with open Q&A and transparent company updates

- Implement a peer recognition programme integrated into the team’s daily workflow

- Conduct pulse surveys every 3 weeks and share results transparently with all teams

Initiatives for KR2 (Attrition):

- Introduce stay interviews for top 20% performers to identify retention risks early

- Redesign the compensation benchmarking process using current market data

- Create internal mobility pathways so employees can explore new roles before looking outside

Initiatives for KR3 (Development):

- Partner with 3 external learning platforms to offer on-demand skill development

- Allocate 4 hours per month of dedicated learning time for every employee

- Tie development participation to manager OKRs to create accountability at the leadership level

Notice how the Objective inspires, the Key Results measure three interdependent dimensions of workforce health (engagement, retention, development), and the Initiatives represent specific, actionable bets the team will place to move each Key Result. If the pulse surveys aren’t improving engagement by mid-quarter, the team adds, modifies, or deletes — they don’t wait until Q4 to acknowledge the approach isn’t working.

This is the OKR system in action: direction from the heart, measurement from the head, and execution from the hands.

Contemporary Practices: How OKR DNA Has Evolved

While the foundational structure of Objectives, Key Results, and Initiatives remains unchanged since Andy Grove’s era, contemporary practice has refined how organisations apply the framework:

Company and team OKRs over individual OKRs

Current best practice, endorsed by leading OKR practitioners and even Google’s own Rick Klau (who originally advocated individual OKRs but later reversed his position), favours setting OKRs at the company and team level rather than for individual contributors. Individual OKRs tend to devolve into task lists and risk being conflated with performance evaluations — both of which undermine the framework’s purpose. Teams own OKRs collectively; individuals contribute through their Initiatives.

OKRs decoupled from compensation

Tying OKR achievement directly to bonuses or performance ratings incentivises conservative goal-setting and destroys the aspirational culture OKRs are designed to create. The emerging standard is to use OKRs to inform performance conversations (alongside CFRs — Conversations, Feedback, and Recognition) but not as the sole basis for rewards.

Bidirectional alignment over top-down cascading

Early OKR implementations often cascaded goals rigidly from CEO to department to team. Contemporary practice emphasises bidirectional alignment: approximately 40% of OKRs are set top-down by leadership and 60% are generated bottom-up by teams. This balance ensures strategic coherence while tapping into front-line intelligence and fostering ownership.

AI-assisted OKR drafting and tracking

In 2025, AI-powered OKR tools can suggest Key Results based on historical data, predict whether current progress trajectories will achieve targets, recommend Initiative adjustments, and even flag alignment conflicts across teams. These tools don’t replace human judgment — they augment it, making the OKR cycle more data-driven and responsive.

Integration with Continuous Performance Management

OKRs increasingly operate as part of a broader performance ecosystem that includes weekly check-ins, CFRs, quarterly retrospectives, and ongoing coaching conversations. This integration — what John Doerr calls Continuous Performance Management — replaces the outdated annual review cycle with a living rhythm of goal-setting, execution, learning, and adaptation.

Benefits of Using OKRs

Every goal-setting framework promises results. What makes OKRs fundamentally different — and why they’ve been adopted by organisations from Silicon Valley startups to Indian manufacturing companies, government agencies, and non-profits — comes down to four distinct superpowers. These aren’t abstract benefits. They are structural advantages built into the DNA of the OKR framework that make it uniquely suited to how organisations must operate today.

John Doerr, who popularised OKRs through his book Measure What Matters, described the benefits of OKRs using the acronym FACTS: Focus, Alignment, Commitment, Tracking, and Stretching. At OKR International, after two decades of implementing OKRs across 500+ organisations and 20+ industries, we’ve found that these benefits manifest through four operational superpowers that leaders experience in practice.

Superpower 1: Converting Strategy to Execution

The problem it solves

Most organisations don’t lack strategy — they lack execution. According to research published in Harvard Business Review, approximately 67% of well-formulated strategies fail due to poor execution. The gap between a PowerPoint strategy deck and what actually happens on the ground is where most organisations lose.

John Doerr, who popularised OKRs through his book Measure What Matters, described the benefits of OKRs using the acronym FACTS: Focus, Alignment, Commitment, Tracking, and Stretching. At OKR International, after two decades of implementing OKRs across 500+ organisations and 20+ industries, we’ve found that these benefits manifest through four operational superpowers that leaders experience in practice.

How OKRs solve it

OKRs act as a translation engine that converts annual strategy into quarterly, actionable goals. By limiting each team or individual to 3–5 Objectives per cycle, OKRs force a rigorous prioritisation exercise that most traditional planning processes avoid. This isn’t about doing everything — it’s about choosing the few things that will create the most impact and committing to them with discipline.

The quarterly cadence is critical. Annual goals create a false sense of time abundance — teams defer action because “the year is long.” Quarterly OKRs create productive urgency. When you have 90 days to move the needle on 3–5 measurable key results, procrastination isn’t an option. Every week counts.

What this looks like in practice

A mid-size Indian IT services company we coached had a clear strategy: expand into the European market. But for three consecutive years, the strategy remained on paper. When they adopted OKRs, the strategy was distilled into a single Q1 Objective: “Establish a credible market presence in the UK.” The key results were specific and measurable — two signed pilot clients, one local partnership, and a functioning London-based microsite with 500+ qualified monthly visitors. Within 90 days, the team had signed one pilot client and established two partnerships. The strategy hadn’t changed. The execution mechanism had.

Superpower 2: Creating Higher Levels of Agility

The issue it solves

The pace of change in global markets has made static annual plans dangerously brittle. Economic shifts, technological disruption, regulatory changes, and competitive moves can render a 12-month plan obsolete within weeks. Organisations that evaluate performance only once a year are essentially driving with a rear-view mirror — looking at where they’ve been, not where they’re going.

How it solves it?

OKRs institutionalise agility through their quarterly cycle and the “fail-fast” philosophy embedded in the framework. This doesn’t mean reckless experimentation — it means structured, time-boxed learning. Teams set ambitious goals, run initiatives as experiments, measure results frequently, and pivot when the data tells them to.

The mechanism is the add-modify-delete discipline applied to initiatives. When a team reviews progress mid-quarter and an initiative isn’t yielding results, they don’t wait until year-end to acknowledge it. They add something new, modify the current approach, or delete what isn’t working — in real time. This rhythm of regular check-ins (weekly or biweekly) and mid-quarter recalibrations is what keeps organisations responsive without being chaotic.

The critical distinction

Agility in the OKR framework is not about changing objectives constantly. Objectives should remain stable within a quarter — they represent your strategic direction. What changes are the initiatives — the bets you place to achieve those objectives. Be passionate about your objectives, be dispassionate about your initiatives. This distinction is what prevents “agile” from becoming a euphemism for “directionless.”

Superpower 3: Achieving Greater Alignment of Goals and Efforts

The pain point it addresses

One of the most pervasive diseases in organisations is what we call the “systemic disconnect” — teams working hard in their silos, each optimising for their own goals, without awareness of how their work connects to (or conflicts with) what other teams are doing.

Consider a real scenario: a cell phone company’s procurement team is unable to secure enough chips on time. Downstream, the product development team’s goal of launching a new device in Q2 becomes unachievable — not because of a product failure, but because the two teams’ goals were never connected in the first place. This systemic disconnect is the silent killer of organisational performance.

How this is managed with OKRs?

OKRs create alignment through three complementary mechanisms:

Vertical alignment (top-down): Company-level OKRs cascade into team-level OKRs, ensuring that every team’s goals contribute to the organisation’s strategic priorities. When a company sets an annual objective to “Achieve market leadership in Southeast Asia,” the sales, marketing, product, and operations teams each create OKRs that directly support this objective.

Bottom-up alignment: Unlike traditional MBO-style cascading, OKRs encourage individuals and teams to propose their own objectives that contribute to organisational goals. This taps into the collective intelligence of the organisation — the people closest to customers and operational realities often see opportunities and risks that leadership cannot.

Horizontal (cross-functional) alignment: This is the most powerful and most underutilised form of OKR alignment. When the procurement team and the product team can see each other’s OKRs — transparently, across the organisation — they can identify dependencies, coordinate timelines, and collaborate proactively rather than discovering misalignment after it’s too late.

The transparency principle

OKR transparency is non-negotiable. When all OKRs — from the CEO to front-line teams — are visible to everyone in the organisation, silos become structurally difficult to maintain. People can see what others are working on, identify where they can contribute, and flag conflicts before they become crises. This transparency also creates a healthy form of peer accountability that no amount of top-down management reporting can replicate.

Superpower 4: Focusing on Value Creation Over Activity

The mindset issue

Most goal-setting systems inadvertently reward busyness rather than impact. When employees are measured on activities — calls made, reports written, meetings attended, interviews conducted — the natural incentive is to maximise volume rather than quality. The result is a workforce that is perpetually busy but not necessarily productive, and certainly not fulfilled.

What OKRs do to tackle this issue?

OKRs fundamentally reframe performance measurement from outputs (what you did) to outcomes (what changed because of what you did). This single shift transforms how people think about their work.

Compare two hiring managers:

Manager A (activity-based goal): “Conduct 10 interviews per day.” Manager A’s work becomes transactional and monotonous. Success is defined by volume, not quality. There’s no ownership over whether the right people are actually being hired, how long they stay, or whether they perform well.

Manager B (outcome-based OKR): “Build a high-performance talent pipeline.” KR1: Reduce time-to-hire from 90 days to 45 days. KR2: Achieve 90-day new hire retention rate of 95%. KR3: Increase offer acceptance rate from 65% to 85%.

Manager B has autonomy over how to achieve these outcomes. Perhaps she redesigns the candidate experience, partners with niche recruitment platforms, or introduces structured scorecards. The key results measure the outcomes that matter. The initiatives are her experiments to achieve them. This ownership leads to greater job satisfaction, deeper engagement, and — critically — better results for the organisation.

The principle in practice

Well-crafted key results are always outcome-based, never activity-based. Every time you write a key result, ask yourself: “Does this measure what changed, or does this measure what we did?” If it measures what you did, it’s an initiative, not a key result. Move it to the initiatives column and find the outcome it was supposed to produce.

The Multiplier Effect: When All Four Superpowers Work Together

These four superpowers don’t operate in isolation — they create a compounding effect. When strategy is converted into focused quarterly goals (Superpower 1), those goals are pursued with agility and rapid learning (Superpower 2), aligned across every team in the organisation (Superpower 3), and measured by the value they create rather than the activity they generate (Superpower 4), the organisation becomes fundamentally more effective than the sum of its parts.

This is why OKRs are not just a goal-setting tool. They are a management operating system — a rhythm of planning, executing, measuring, and recalibrating that keeps the entire organisation moving in the same direction, at speed, with purpose.

OKR Examples Across Business Functions

The best way to understand OKRs is to see them in action. Below are five OKR examples across different business functions — each written the way we coach our clients at OKR International. Notice that every example includes all three DNA components: an inspiring Objective, measurable Key Results with baselines and targets, and actionable Initiatives. Pay attention to the coaching notes — they highlight the common mistakes we see teams make and how to avoid them.

OKR Examples of 45+ Functions | OKR Examples Across 30+ Industries

1. Sales OKR Example

Objective: Become the undisputed leader in enterprise sales in our region.

Key Results:

- KR1: Increase enterprise deal win rate from 18% to 35%

- KR2: Grow average deal size from ₹12L to ₹20L

- KR3: Reduce average sales cycle from 110 days to 60 days

Initiatives:

- Launch a dedicated enterprise solution-selling training programme for the sales team

- Develop 5 industry-specific case studies for use in enterprise pitches

- Implement a deal review cadence with weekly pipeline inspection meetings

2. HR / People OKR Example

Objective: Build a talent acquisition engine that consistently attracts best-fit candidates.

Key Results:

- KR1: Reduce time-to-hire from 90 days to 45 days

- KR2: Increase offer acceptance rate from 62% to 88%

- KR3: Achieve new hire 90-day retention rate of 95% (currently 78%)

Initiatives:

- Redesign the candidate experience journey from application to onboarding

- Partner with 3 niche recruitment platforms for specialised roles

- Introduce structured interviewing scorecards to reduce hiring bias and improve consistency

3. Marketing OKR Example

Objective: Establish our brand as the most trusted voice in our industry.

Key Results:

- KR1: Increase organic website traffic from 25,000 to 60,000 monthly sessions

- KR2: Grow marketing qualified leads (MQLs) from 200 to 500 per quarter

- KR3: Achieve a domain authority score improvement from 35 to 50

Initiatives:

- Publish 12 high-value pillar articles targeting top-of-funnel search queries

- Launch a monthly thought leadership webinar series featuring industry experts

- Secure guest contributions on 8 industry publications for backlink development

4. Product / Engineering OKR Example

Objective: Deliver an onboarding experience that users genuinely love.

Key Results:

- KR1: Increase Day-7 user activation rate from 28% to 55%

- KR2: Reduce onboarding drop-off rate from 42% to 12%

- KR3: Achieve in-app onboarding satisfaction score of 4.6/5 (currently 3.2)

Initiatives:

- Conduct 20 user interviews to map the current onboarding friction points

- Build and A/B test a guided interactive walkthrough for new users

- Reduce onboarding steps from 11 to 5 by eliminating non-essential data collection

5. Customer Success OKR Example

Objective: Create customers so successful they become our most powerful growth engine.

Key Results:

- KR1: Increase Net Promoter Score (NPS) from 32 to 55

- KR2: Improve annual customer retention rate from 74% to 92%

- KR3: Generate 30% of new revenue from customer referrals and expansions (currently 12%)

Initiatives:

- Implement a structured quarterly business review (QBR) programme for top 20 accounts

- Launch a customer health scoring system to identify at-risk accounts 60 days before renewal

- Create a customer advocacy programme with referral incentives and co-marketing opportunities

All You Need To Know About OKRs

What is the difference between OKRs and KPIs?

OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) and KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) are complementary, not competing frameworks. KPIs are standalone metrics that monitor the ongoing health of your business — think of them as a dashboard showing where you are right now. OKRs, on the other hand, are a goal-setting and execution system that defines where you want to go and how you'll measure progress getting there. KPIs track the status quo; OKRs drive strategic change. A declining KPI often becomes the trigger for setting a new OKR. For example, if your KPI shows customer retention has dropped to 70%, you might set an OKR with the objective "Build a world-class customer success engine" and key results like "Increase retention from 70% to 85%" and "Achieve NPS score of 50+." At OKR International, we often say: OKRs are KPIs with direction, purpose, and soul.

How many OKRs should a team or company have?

The recommended limit is 3 to 5 Objectives per quarter, with 3 to 5 Key Results per Objective. This constraint is intentional — it forces prioritization, which is one of the core superpowers of the OKR framework. Having more than 5 objectives per cycle dilutes focus and leads to scattered execution. Fewer than 3 may underutilize the team's capacity. At the company level, 3–5 strategic OKRs cascade into team-level and individual OKRs, each maintaining the same 3–5 discipline. The total number of OKRs across an organization can reach into the hundreds, but at any single level — company, team, or individual — the 3-to-5 rule holds.

How often should OKRs be reviewed?

OKRs should be reviewed at multiple cadences. The standard practice is to set OKRs quarterly (the OKR cycle), but within each quarter, teams should conduct weekly or biweekly check-ins to track progress on key results and assess whether initiatives are moving the needle. A mid-quarter review allows for course correction — adding, modifying, or deleting initiatives that aren't working. At the end of each quarter, a formal OKR retrospective evaluates what was achieved, what was learned, and what carries forward. Annual strategic OKRs are also reviewed at the start of each quarter to ensure alignment. The discipline of frequent check-ins is what separates OKRs from traditional annual goal-setting — and it's where 80% of OKR success is determined.

What is the difference between committed and aspirational OKRs?

Committed OKRs (sometimes called "roofshot" OKRs) are goals the team is expected to fully achieve — typically representing critical business commitments with a target completion of 100%. Aspirational OKRs (also called "moonshot" OKRs or stretch goals) are deliberately ambitious goals where achieving 60–70% is considered a strong result. Google popularized this distinction: aspirational OKRs push teams beyond their comfort zones and drive innovation, while committed OKRs ensure that non-negotiable business priorities are delivered. A healthy OKR set typically includes a mix of both. The key is to clearly label each OKR as committed or aspirational so teams calibrate their effort and expectations accordingly.

Should OKRs be tied to performance reviews or compensation?

The widely recommended best practice is to not tie OKRs directly to compensation or performance ratings. When OKRs are linked to bonuses or evaluations, teams are incentivized to set conservative, easily achievable goals — which defeats the purpose of the framework. OKRs thrive in an environment of psychological safety where teams can set ambitious stretch goals, experiment boldly, and learn from failure without fear of penalty. Instead, organizations should evaluate performance based on the quality of effort, learning velocity, and how intelligently teams adapted their approach — not simply whether they hit 100% on every key result. OKRs inform performance conversations but should not be the sole basis for rewards.

What are some good OKR examples?

Here are OKR examples across three common business functions:

Sales OKR: Objective: Become the dominant player in the enterprise segment. KR1: Increase enterprise deal close rate from 15% to 30%. KR2: Grow average enterprise deal size from ₹10L to ₹18L. KR3: Reduce enterprise sales cycle from 120 days to 75 days.

HR OKR: Objective: Build a talent acquisition engine that attracts top-tier candidates. KR1: Reduce time-to-hire from 90 days to 45 days. KR2: Increase offer acceptance rate from 60% to 85%. KR3: Achieve a candidate experience NPS of 70+.

Product OKR: Objective: Deliver an onboarding experience users love. KR1: Increase Day-7 activation rate from 30% to 55%. KR2: Reduce onboarding drop-off rate from 40% to 15%. KR3: Achieve onboarding satisfaction score of 4.5/5.

Notice how every key result is outcome-based (not activity-based), has a clear metric, a baseline, and a target.

What are CFRs and how do they relate to OKRs?

CFRs — Conversations, Feedback, and Recognition — were introduced by John Doerr in his book Measure What Matters as the essential companion to OKRs. While OKRs provide the structure for goal-setting and measurement, CFRs provide the human element needed to make them work. Conversations are regular, authentic exchanges between managers and team members about OKR progress, obstacles, and growth. Feedback is continuous, bi-directional input that helps individuals and teams course-correct in real time. Recognition is peer-to-peer and manager-to-team acknowledgement of contributions and progress. Together, OKRs and CFRs form what Doerr calls "Continuous Performance Management" — replacing the outdated annual review cycle with an ongoing rhythm of goal-setting, dialogue, and improvement.

Can OKRs be used for personal goals, not just business?

Yes. While OKRs originated in the corporate world, the framework is equally powerful for personal goal-setting. Personal OKRs apply the same discipline — setting 3–5 meaningful objectives with measurable key results — to areas like health, relationships, financial goals, learning, and career development. For example, a personal fitness OKR might be: Objective: Become the fittest version of myself. KR1: Increase average deep sleep from 45 minutes to 90 minutes. KR2: Reduce waistline from 38 inches to 34 inches. KR3: Complete 3 unassisted pull-ups by end of quarter. The key difference from a typical New Year's resolution is the measurement discipline and the regular review cadence — you're not setting and forgetting, you're tracking weekly and adjusting initiatives continuously.

How long does it take to implement OKRs in an organization?

OKR implementation is a journey, not a one-time event. Most organizations see initial results within 2–3 quarters of disciplined practice, but full cultural adoption typically takes 4–6 quarters (1 to 1.5 years). The first quarter is often a learning cycle where teams get comfortable with writing OKRs, establishing check-in rhythms, and understanding the difference between activities and outcomes. Common implementation approaches include starting with a pilot team or department, training OKR champions, and gradually expanding across the organization — rather than attempting a company-wide rollout on day one. Working with an experienced OKR coach can significantly accelerate this timeline and help avoid the 15 most common OKR implementation mistakes.

OKR vs KPI

What’s the Difference and Do You Need Both?

One of the most common questions we hear from leaders considering OKRs is: “We already track KPIs — why do we need OKRs too?” It’s a fair question, and the answer isn’t that one replaces the other. OKRs and KPIs serve fundamentally different purposes, and high-performing organizations need both. Understanding the distinction is critical before you begin your OKR journey.

What Is a KPI?

A KPI (Key Performance Indicator) is a quantifiable metric that monitors the ongoing health and performance of your business. Think of KPIs as your organisation’s vital signs — they tell you how things are running right now. KPIs are typically stable, tracked continuously (monthly, quarterly, or annually), and reflect business-as-usual performance.

Common KPI examples include monthly revenue, customer churn rate, employee attrition, net profit margin, average ticket resolution time, and production defect rate.

KPIs answer one question: “How are we performing?”

What Is an OKR?

An OKR (Objectives and Key Results) is a goal-setting and execution framework that defines what you want to change, improve, or achieve — and how you will measure whether you’re getting there. OKRs are dynamic, set quarterly, and are designed to push the organisation beyond its current state.

OKRs answer a different question: “Where do we want to go, and how will we know we’ve arrived?”

The Core Difference: Monitoring vs. Movement

The simplest way to understand the OKR vs KPI distinction is this: KPIs monitor the status quo. OKRs change it.

KPIs are like the dashboard of your car — speed, fuel level, engine temperature. They tell you how the car is performing at any given moment. OKRs are the destination you’ve typed into the navigation system and the route you’ve chosen to get there. You need the dashboard to drive safely. You need the navigation to drive purposefully. Neither replaces the other.

At OKR International, we often tell our clients: “OKRs are KPIs with direction, purpose, and soul.” A KPI tells you where you are. An OKR tells you why it matters to get somewhere better, and how fast. A KPI is doing things right – an OKR is doing the right things.

| Dimension | KPI (Key Performance Indicator) | OKR (Objectives and Key Results) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Monitor ongoing business performance | Drive strategic change and improvement |

| Nature | Static metric | Dynamic goal-setting framework |

| Time horizon | Ongoing — tracked month over month, year over year | Time-bound — typically quarterly cycles |

| Direction | Backward-looking (lagging indicator): “Did we hit the target?” | Forward-looking (leading indicator): “Where do we need to be?” |

| Scope | Single metric (e.g., churn rate = 5%) | System of components: Objective + Key Results + Initiatives |

| Ambition level | Targets are attainable and reflect realistic performance | Targets are often stretch goals (60-70% achievement = success) |

| Flexibility | Rarely changes — the same KPIs are tracked quarter after quarter | Changes every quarter based on strategic priorities |

| Collaboration | Typically set by management | Combines top-down, bottom-up, and cross-functional input |

| Link to compensation | Frequently tied to bonuses and performance reviews | Best practice is to decouple from compensation |

| Transparency | Often visible only to relevant teams or managers | Visible across the entire organisation |

How a KPI Becomes an OKR: A Real-World Example

This is where theory becomes practice. Let’s walk through a scenario that shows exactly how KPIs and OKRs work together.

The situation: You are the Head of Customer Success at a SaaS company. Your team tracks several KPIs, including:

- Customer retention rate: 72% (target: 85%)

- Net Promoter Score (NPS): 28 (target: 50)

- Average support ticket resolution time: 48 hours (target: 24 hours)

Your retention KPI has been declining for two consecutive quarters. The KPI has done its job — it has surfaced the problem. But the KPI alone cannot fix it. It tells you what is underperforming, not why or how to change it. This is exactly where OKRs step in.

The OKR you set for Q3:

Objective: Transform our customer success function into a retention and growth engine.

Key Results:

- KR1: Increase customer retention rate from 72% to 85%

- KR2: Improve NPS from 28 to 50

- KR3: Reduce average ticket resolution time from 48 hours to 18 hours

- KR4: Generate 20% of new revenue from upsells and referrals within the existing customer base (currently 6%)

Initiatives:

- Implement a customer health scoring model to identify at-risk accounts 45 days before renewal

- Launch quarterly business reviews (QBRs) for top 30 accounts

- Redesign the support escalation process with a dedicated tier-2 response team

- Create a customer advocacy programme with referral incentives

What just happened? The declining retention KPI triggered the OKR. The KPI metric (retention rate) became one of the key results. But the OKR added what the KPI couldn’t.

OKR vs KPI vs MBO vs Balanced Scorecard: A Broader Comparison

Leaders often ask how OKRs compare not just to KPIs, but to other goal-setting frameworks they may have used in the past. Here is a brief comparison of the four most common frameworks:

| Framework | Origin | Cycle | Direction of Goal Setting | Tied to Compensation? | Primary Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPI | Early 20th century | Ongoing | Top-down | Often yes | Monitoring business health |

| MBO (Management by Objectives) | Peter Drucker, 1954 | Annual | Top-down cascade | Yes | Individual accountability |

| Balanced Scorecard | Kaplan & Norton, 1992 | Annual | Top-down | Often yes | Multi-perspective strategy mapping |

| OKR (Objectives and Key Results) | Andy Grove / Intel, 1970s | Quarterly | Top-down + bottom-up + cross-functional | Best practice: No | Agility, alignment, and ambitious execution |

Each framework has its strengths. KPIs are essential for performance monitoring. MBOs brought discipline to individual goal-setting. The Balanced Scorecard introduced the idea of measuring strategy across multiple perspectives (financial, customer, internal process, learning and growth). OKRs took the best elements from these predecessors and added quarterly agility, bidirectional alignment, transparency, and a culture of ambitious experimentation.

In practice, most mature organisations use OKRs and KPIs together — with KPIs providing the ongoing performance baseline and OKRs driving the strategic improvements that move those KPIs in the right direction.

Five Common Mistakes When Confusing OKRs with KPIs

From two decades of OKR coaching across 500+ organisations, here are the mistakes we see most often when teams blur the line between OKRs and KPIs:

1. Treating OKRs as a KPI dashboard. If your OKRs look identical quarter after quarter, you’ve created KPIs and labelled them as OKRs. OKRs should change every cycle because your strategic priorities evolve.

2. Writing activity-based key results. “Conduct 15 customer calls per week” is a task, not a key result. A proper key result would be “Increase customer satisfaction score from 3.8 to 4.5.” The calls are an initiative; the satisfaction score is the outcome.

3. Setting too many OKRs. When everything is a priority, nothing is. If you have 12 objectives in a quarter, you have a KPI scorecard, not an OKR set. Stick to 3–5 objectives maximum.

4. Linking OKRs directly to bonuses. This incentivises conservative goal-setting and kills the aspirational nature of OKRs. Keep KPIs in your performance review structure and OKRs in your strategic execution structure.

5. Using OKRs without initiatives. An objective with key results but no initiatives is a wish list. Initiatives are the bets you place, the experiments you run, and the levers you pull to move the key results. Without them, you’ve set a destination with no route planned.

| Framework | Origin | Cycle | Direction of Goal Setting | Tied to Compensation? | Primary Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPI | Early 20th century | Ongoing | Top-down | Often yes | Monitoring business health |

| MBO (Management by Objectives) | Peter Drucker, 1954 | Annual | Top-down cascade | Yes | Individual accountability |

| Balanced Scorecard | Kaplan & Norton, 1992 | Annual | Top-down | Often yes | Multi-perspective strategy mapping |

| OKR (Objectives and Key Results) | Andy Grove / Intel, 1970s | Quarterly | Top-down + bottom-up + cross-functional | Best practice: No | Agility, alignment, and ambitious execution |

Each framework has its strengths. KPIs are essential for performance monitoring. MBOs brought discipline to individual goal-setting. The Balanced Scorecard introduced the idea of measuring strategy across multiple perspectives (financial, customer, internal process, learning and growth). OKRs took the best elements from these predecessors and added quarterly agility, bidirectional alignment, transparency, and a culture of ambitious experimentation.

In practice, most mature organisations use OKRs and KPIs together — with KPIs providing the ongoing performance baseline and OKRs driving the strategic improvements that move those KPIs in the right direction.

Do You Need OKRs, KPIs, or Both?

The short answer: both. Every organisation needs KPIs to monitor operational health. And every organisation that wants to grow, innovate, or transform needs OKRs to drive strategic change. The question isn’t OKR or KPI — it’s understanding when to use which, and how they feed into each other.

A useful rule of thumb from our coaching practice at OKR International:

- If you want to track it → KPI

- If you want to change it → OKR

- If a KPI is underperforming and you want to fix it → That KPI becomes a key result inside a new OKR

About the Author

Nikhil Maini is the Founder and Managing Director of OKR International, based in Dubai, UAE — one of the world’s leading consulting brands specialising in full-stack OKR implementation, certification, and coaching. He is also the CEO of Synergogy and Chairman & Managing Director of Seven People Systems Pvt. Ltd.

With 29+ years of experience in organisational development, strategy execution, and leadership coaching, Nikhil has worked with 500+ organisations across 25+ industries — from Fortune 500 enterprises to high-growth startups — helping them translate strategy into measurable results through the OKR framework.

Nikhil is the creator of the OKR-BOK™ (OKR Body of Knowledge), a globally recognised framework that integrates behavioural science with strategic agility. He is a Forbes Business Council member, a certified behavioural analyst, and a recognised thought leader in OKR transformation, Agile Performance Management, and culture change.

Nikhil’s mission is to help organisations worldwide become more agile, more collaborative, and more successful — one OKR at a time.

Connect with Nikhil: LinkedIn

Ready to Implement OKRs in Your Organisation?

OKR Foundation Course

OKR-BOK™ Certified Practitioner

OKR-BOK™ Certified Coach